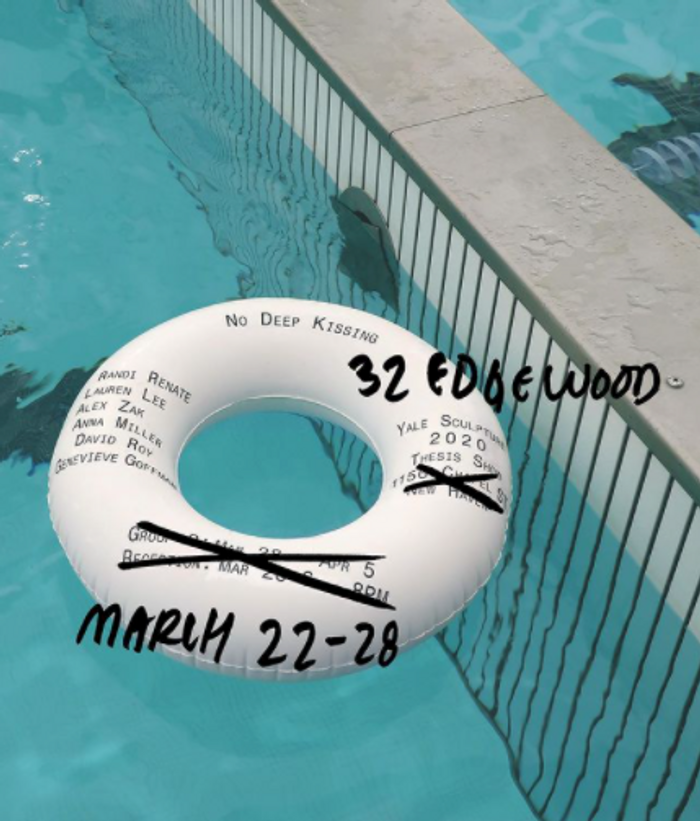

Delayed by a year and far overdue, the second half of No Deep Kissing, Yale School of Art’s Sculpture Group 2 graduates of 2020 Thesis show opens Monday, March 22nd at 32 Edgewood. Featuring new works and installations from Genevieve Goffman, Lauren Lee, Anna Alvina Miller, Randi Renate, David Roy, and Alex Zak, this exhibition celebrates not only the culmination of the artists’ graduate school careers, but also the continued dedication to their practices in a year of great upheaval and duress. Even in the quietest of times, graduating into the world can be a difficult and disorienting task—we often change in ways we don’t expect with people whose faces are only recently becoming familiar to us. But now, as the world slowly re-emerges from the carnage of a year isolated and fearful, we see the work still persists—though not as we may remember it. Let us begin the process of finding our communities in their wholeness once more and hold space together, even if the rule of no deep kissing remains.

No Deep Kissing

Yale Class of 2020 Sculpture MFA Thesis Show Group 2

March 22-28, 2021

32 Edgewood Gallery, New Haven, CT 06511

Artists:

Genevieve Goffman

Lauren Lee

Anna Alvina Miller

Randi Renate

David Roy

Alex Zak

Website design:

by Harin Jung, Yale Graphic Design MFAs ‘21

Poster design:

by Jinu Hong, Kyla Arsadjaja, Orysia Zabeida, Yale Graphic

Design MFAs ‘20

Documentation Photography:

by Merik Goma

Virtual Exhibition Walk-Through ↗

Lauren Lee

Lauren Lee

Lauren Lee

Lauren Lee

writing

Dog In Training: Review by Kathryn Gruszecki

A series of drawings depicting the process of human taxidermy

hang alongside an actual taxidermied fox— hollowed out, skinned,

and the face no longer attached. The fur, the skin, and the face

make up three objects. The skin of the fox is intricately set up

to purge the tennis balls it was trained to catch. The fox, like

a dog, is in the process of being domesticated.

The body of the fox sits next to its skin. It’s visibly soft fur

drives the urge to pet, yet it remains a hollow, faceless, empty

vessel. This empty body becomes the pictorial representation of

the process of becoming an object— one envisioned by the

taxidermist. The taxidermist gives the dead fox a new life

without knowing any details of the one it had prior. The title

of the series, Dog In Training, depicts the taxidermist as one

that fills the fox up to shape it into what it desires. The fox

is now a hound. She sits to be pet, fetches the ball in motion,

and obeys the orders of the artist.

The fox’s face is hung on the opposing wall helplessly staring

at its still, stuffed, body and flaccid skin as it takes on the

form of the artist’s imaginary.

Lauren Lee’s drawings fill the wall closest to the objects. It

is in this moment we meet Kevin and the artist’s narration of

human taxidermy. In a series of three, Kevin’s eyes are gorily

removed and replaced. Then, like the fox, his face is delicately

sliced and removed. In the final step, his head is stuffed with

cotton.

The relationship between the objects and the drawings is one

that relates closely to being desired and desiring. The Lacanian

notion of desire is always, “… the desire of the Other.” Which

Lacan claims is the process of “… always asking the Other what

they desire” (38, Lacan, Jacques. My Teaching; Verso Books,

2009.) The taxidermic object is emptied with all that makes it a

fox or Kevin and is stuffed into becoming the object of the

taxidermist’s desire.

The tension of this relationship to desire and being desired is

not absent of both pleasure and pain— it is depicted in Lee’s

drawings as masochistic. Kevin’s head is enclosed in a cage

while the artist holds a flower to his nose offering him a treat

of the flower’s smell.

Again, Kevin has hot tea poured down his mouth- symbolic of both

an act of care but painful as we can imagine the heat of the tea

burning the subject’s mouth.

In trying to become what the other desires we find pleasure in

pleasing them but pain in the transformation. There also is pain

in knowing that one could never be the perfect image in the eyes

of the other— a feeling of disappointment as we always fall

short— spitting up the tennis balls we were trained to catch

because catch is not a game meant for a fox. Lauren Lee is both

the fox and the human taxidermist, simultaneously an object of

desire and one that desires.

Anna Alvina Miller

Anna Alvina Miller

Anna Alvina Miller

Anna Alvina Miller

Anna Alvina Miller

Anna Alvina Miller

Anna Alvina Miller

writing

Lifelines: Anna Alvina Miller’s In the Blue (2021) by Rachel Tang

To locate ourselves and our sense of home in the expanse of the

unknowable, we must learn the distances between stars, rehearse

emergency procedures, and calibrate our instruments of

navigation. Seldom do we allow ourselves to venture into the

blue, to sit with the unknowable opacity of water. Yet so often

do we ask our waters—whether they be rivers, oceans, or seas—to

bear the anxieties we project upon the mysteries they embody. To

live out on the water, as Anna Alvina Miller has been doing with

her partner, is to become accustomed to sitting with the

discomfort of these unknowns; you exist according to the whim of

the elements, what weather the winds will bring in, or how the

waves will roll beneath your feet.

Miller’s work, In the Blue, invites us to become familiar with

the textures of not knowing. Here, her thirty-five foot home on

the water is deconstructed, stripped down to the parts most

essential to safety and navigation. Two twin steel bodies are

wrapped with a continuous length of rope, forming a

foreshortened kind of a tentacular constellation. These dual

structures are held together, with some slack, by the very same

ropes which constitute them. This is the moment that the

celestial meets the terrestrial, the moment between that which

is tangible and that which is just out of reach.

A rope, pristine and uniform in its undulations, is wrapped

around one of the steel bodies. Indelibly intricate stitching is

revealed upon closer inspection. On this celestial twin, the

rope unfolds around a tide clock, with its verso bearing a

traditional clock, gesturing towards our insistence on measuring

the present, making time paradoxically slip past us in two

directions. To not have a clock aboard is a cardinal sailing

sin, as time spent on the land can feel dangerously different

than time spent at sea, as one’s temporal sensibilities are

liquidated, quickly becoming difficult to grasp.

In the presence of epistemological gaps which threaten our

stability, protection and small comforts become important.

Broken down to its smallest fibers, a different, dilapidated

rope creates a protective wrapping around the other body, the

terrestrial twin. This kind of rope, called “baggy wrinkle” is

an old sailor’s process that repurposes otherwise useless

materials into a layer of protection. This terrestrial body also

bears a barometer and comfortmeter to measure pressure,

temperature and humidity; peculiar machines regulating our

proximities to the natural forces around us.

The rope that supports the tide clock on the celestial structure

extends out like a lifeline to its twin. In nautical terms, a

lifeline is many things: a line shot to another ship in

distress, a line used to lower divers into the depths, a line

that attaches a person to their vessel. The diagonal line in

one’s palm, thought to indicate the length of one’s life, is

another kind of lifeline, etched into our own bodies, perhaps

another attempt to compress the unknown into something

measurable. Here, this continuous length of rope between twin

bodies loops and twists to form multiple infinity signs, a

lifeline ad infinitum.

This past year, we have been plunged into the blue. For many

reasons, time feels different and we feel particularly

vulnerable. When we travel into the blue, we worry that there is

a chance that we might become adrift or disappear completely.

Here, however, Miller offers us a lifeline. In the Blue is a

promise that we are still free to wander, knowing we will safely

return to our vessels.

Randi Renate

Randi Renate

Randi Renate

David Roy / BLACKNASA

David Roy / BLACKNASA

writing

text by Holly Bushman

In August 2019 David Roy took a cross-country motorcycle trip

from Inglewood, CA to New Haven, CT. Road trips have a way of

climbing into our minds and resurfacing in unexpected ways: we

remember billboards and gas station meals, unfamiliar faces and

unremarkable stretches of highway. On this particular trip,

David was confronted with the realities of life in America: the

ecological damage, economic depression, and enduring racism that

marks so much of this country, alongside fading reminders of

American exceptionalism and the manufactured symbols of past

greatness, a greatness that for many Americans has never

existed.

Yet David’s trip has informed his practice as a powerful means

of thinking through contemporary American identity and its

potential futures. The founder of BLACKNASA, a space program

committed to peaceful and meaningful exploration, David builds

rockets which reclaim the power of technology as a tool for

good. His rocket launches are events which unite and inspire,

and remind us of the incredibly human capacity for joy and

wonder.

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

Alex Zak

writing

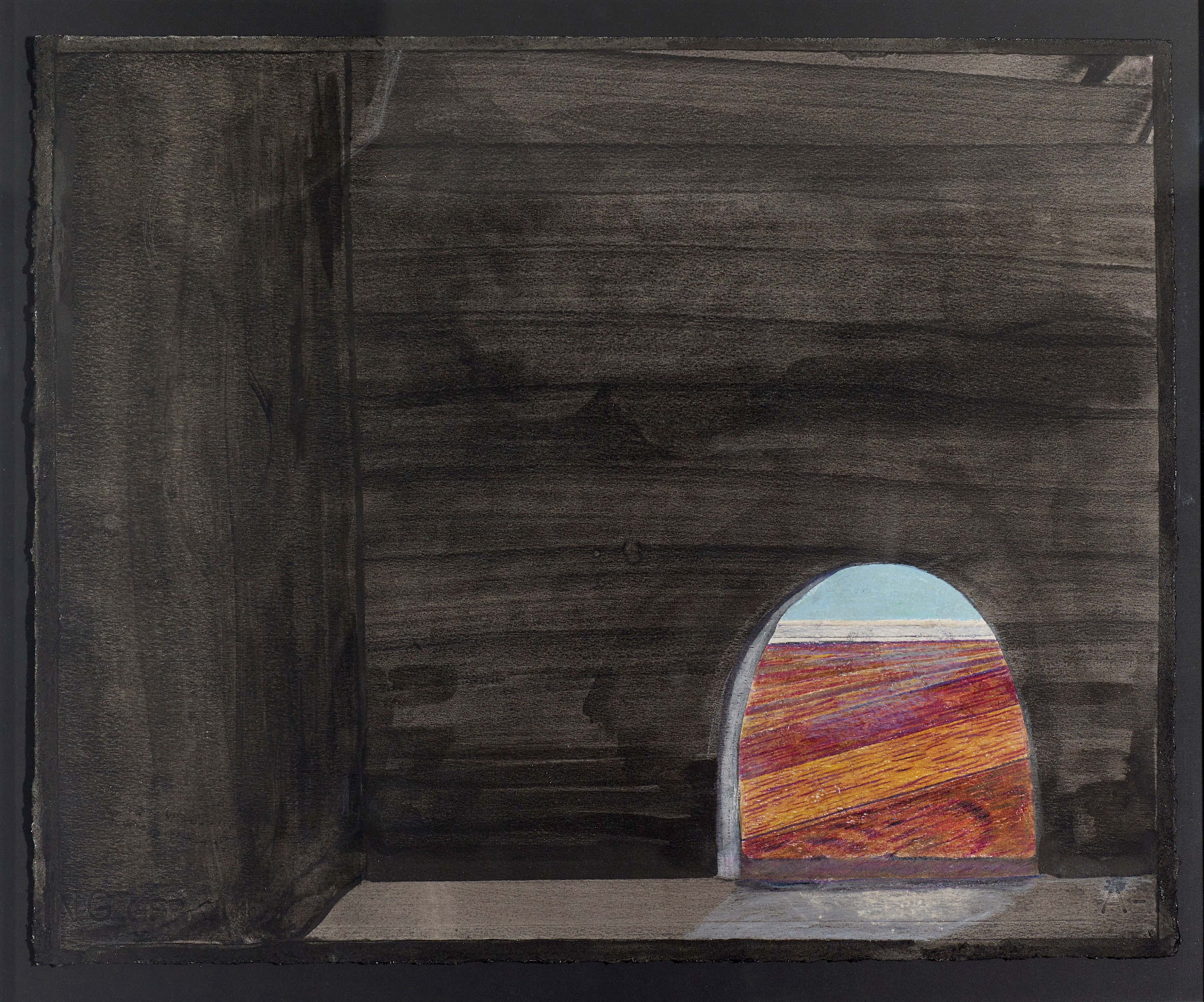

On Things That Recede by Joseph Zordan

“Spring break… spring break forever…” — James Franco as Alien in

Spring Breakers (2012)

Florida nights are typically associated with bright club lights

flashing on the shore and young tourists screaming until dawn. A

land founded on the myth of eternal light, youth, and excess for

Spanish conquistadors, reiterated time and time again within

popular culture, Florida remains a locus of pleasure and

debauchery within the American imaginary. Within Alex Zak’s most

recent installation bringing together drawing, installation, and

sculpture, however, we are asked to think of a night that does

not scream, but recedes quietly into the shadows instead, a soft

breeze between the leaves. In the quiet of Zak’s rendered night,

away from the lights and noise of urbanity, a forest stands

hushed and still; a fountain runs dry, and a sign becomes

illegible. In this voided landscape of the new moon, how quickly

does your own hand become unfamiliar to you?

This defamiliarization—whether it be of material,

myth, self, or image—is a central aspect of many of the works

within the installation. Common legends of the fountain of youth

among early European settlers and explorers of the tropics hover

around What Spoils the Fountain, Poisons the Well. The

gravitational center of Zak’s constellated installation, this

work is a barren well built against a sheetrock wall incised

with three windows cascading downward. Tiled with unpainted

scored-sheetrock and imitation terrazzo, also made of sheetrock,

on a wooden stair armature leading to the barren pool, this

architectural piece seems not only drained of its water, but of

the very magic and vitality it may have once contained. The

sheetrock crumbles and splays outward from the piece, seemingly

exhausted by the weight of history and image it was meant to

carry. A material typically meant to recede behind works within

art galleries, sheetrock here takes a lead role, unmistakable

and unavoidable. In foregrounding sheetrock, Zak denaturalizes

the material, along with the mythos it represents.. Embedded

within the stairs, a rusted sword ornamented with hot pink and

pearl-esque plastic bead necklaces seems to locate the wound

which bled this well dry. Its form seems to place the colonial

aspirations for immortality and the Edenic infinity of natural

resources as an unwinnable prize, which comes at a particularly

poisonous cost to Native and Indigenous inhabitants and

lifeways. For the artist, it seems that colonial fantasies

collapse under the weight of their imposed promises, an

unsustainable system meant to crumble beneath settlers’ feet.

The moons orbiting this central work, Indiscriminate

Collector and Burnt-Out Chariot, locate these colonial histories

and broken vows further. The former, an assemblage of iridescent

pen shell fragments hoisted on a copper frame, congeal into the

image of a metal detector. A video, nestled within the work’s

screen, of plant life from a relative-of-the-artist’s backyard

loops back in on itself over and over again. As the wind blows

and the sun shines on the recorded botany, strange, shifting,

kaleidoscopic colors shimmer across the plants’ surface; the

water from the surrounding area contains enough metals to be

absorbed within the tissue of the plants themselves. These

collisions between non-human life and the metallic—whether of

the plants in the video or the composition of the metal detector

itself—rehearse the hybridization for which the American tropics

are well known. Within these combined forms, colonial desires

and aspirations again become evident. Indiscriminate Collector’s

iridescent and shining body conjures the aspirational search for

wealth along the shore and tropics that gave way to many of

these hybrid bodies from earliest modes of colonialism to today.

Whether it be from a shipwreck, plantations, or tourists’ loose

pockets, myths of abundance and economic mobility remain.

Ecology, for Zak, seems to go far beyond even that which is

breathing, and brings a liveliness to metals which infiltrate

boundaries of the epidermis—human and plant alike.

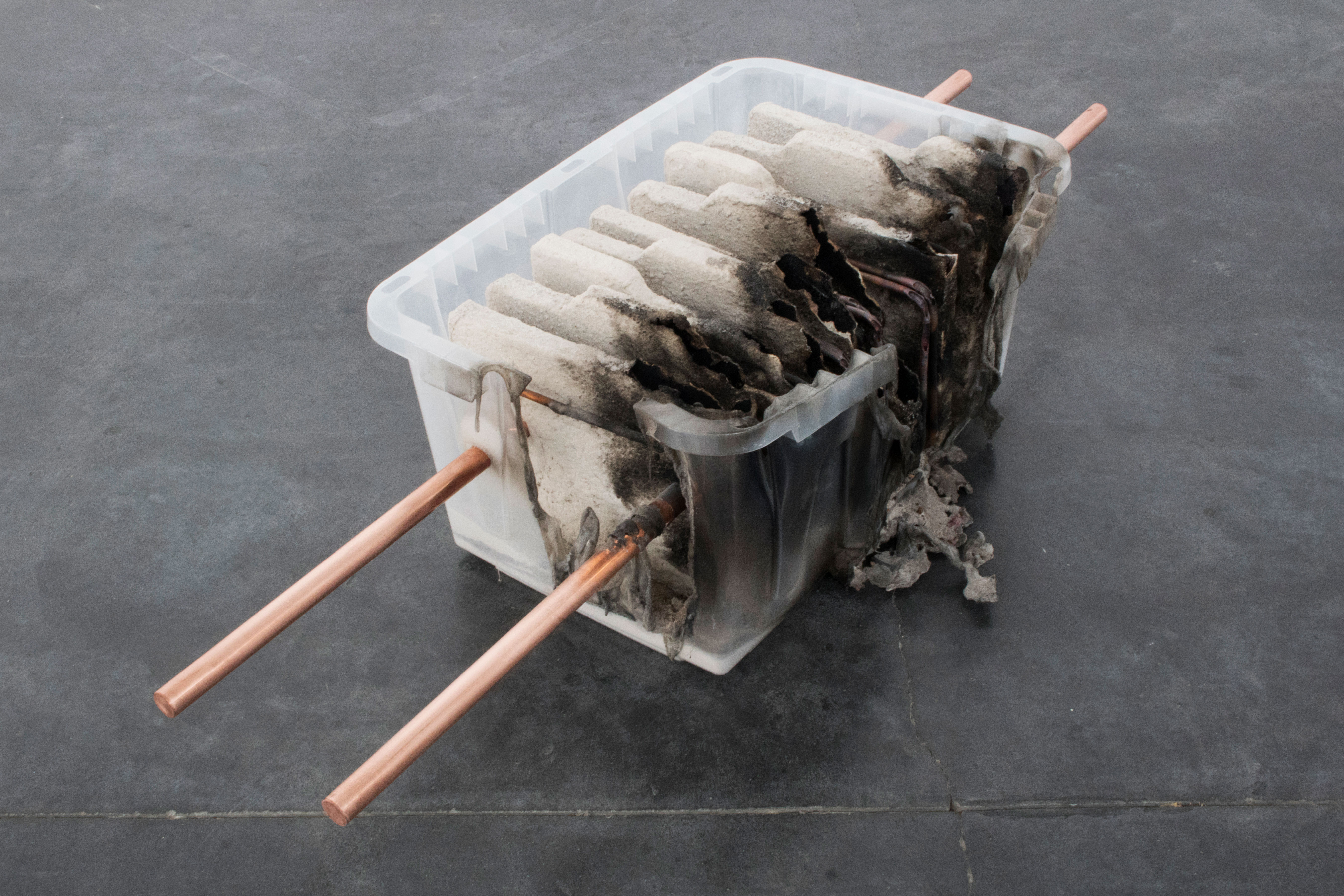

These stories seem to reach their culmination in

Burnt-Out Chariot. Carefully melted, the plastic bin and the

folders within Burnt-Out Chariot seem to still be settling from

their previously overheated state, a small pile of debris of

mixed materials sloping from the bin. But even in its state of

ruin, its copper handles gleam, polished and pristine. An

amalgamated object, making the familiar strange yet again. In

the charred remains of transmission, Zak seems to gesture toward

the polemics of history and memory itself: What stories survive?

And for whom? And perhaps more importantly: What history is

destroyed? And for whom?

Yet even in the midst of ruins and collisions, violent and hot,

there remains the possibility of what is to come. In the bizarre

alliances between materials and images, human and non-human,

living and nonliving, something else seems to be waiting in the

wings. Rather than a platform at the end, the installation seems

to be the stage for what is next. Within the suite of drawings,

nocturnes in their own right, The Morning After reveals a golden

break of dawn. The windows, when catching light just right, cast

beams onto the beads which gleam just like the copper. The

night, however, does not need to dissipate for us to move beyond

it; Zak seems to have made his own stars, whose gleam might

guide us beyond this ruin to someplace else, yet to be imagined.